Solving Copyright and Intellectual Property Issues in Training Generative AI

How about a new Spotify feature? Kurt Cobain x Taylor Swift, anyone?

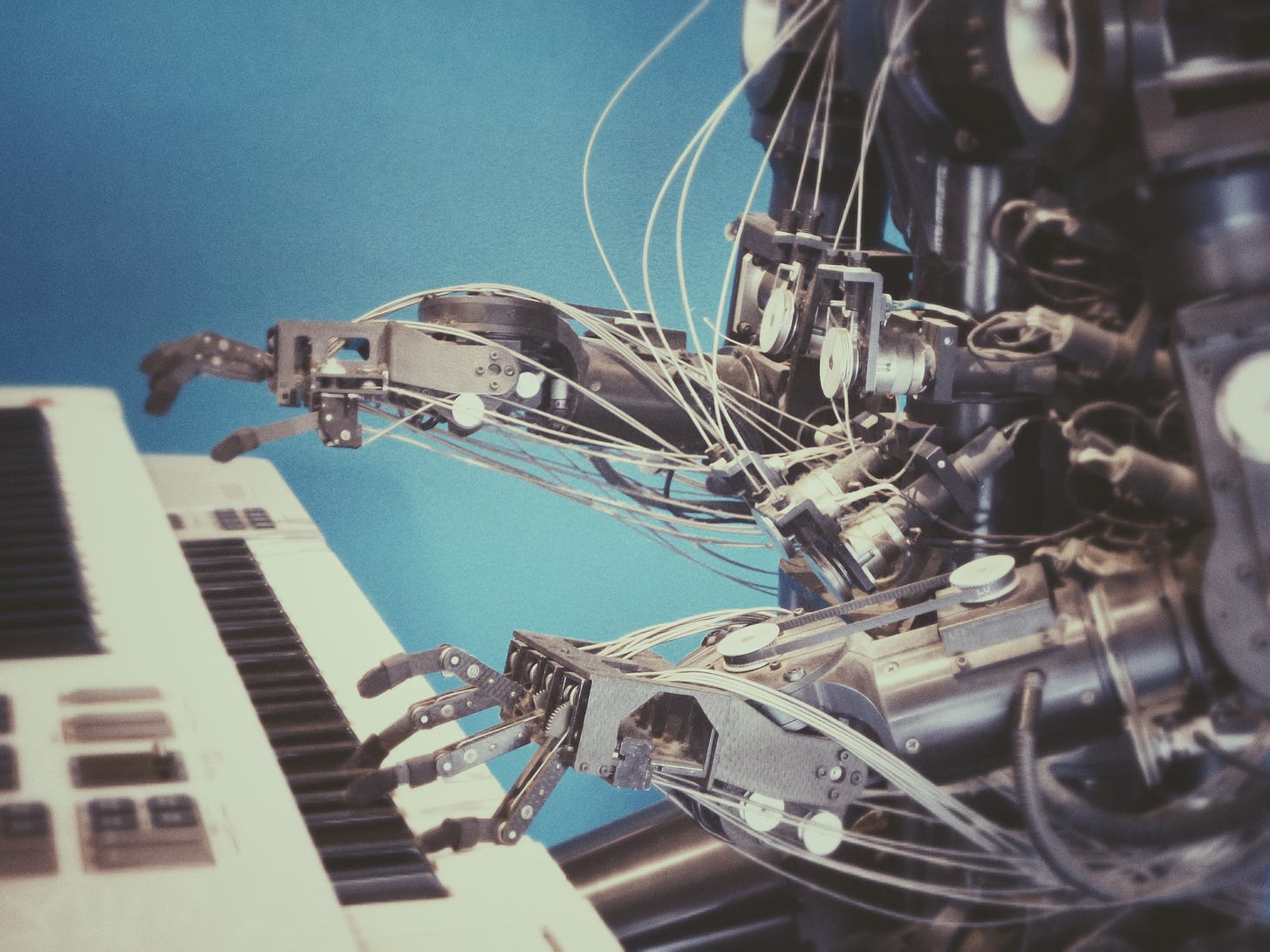

Who needs humans when you can have robots make all the art and creative output? Instead of delving into philosophical ramblings, let’s just say the robots need human creativity in order to make the songs, chat assistants, artwork, and more that has been flooding the internet and making headlines everywhere. From ChatGPT to songs that sound strikingly similar to Drake, generative AI is in the thick of an ongoing battle to determine the legality of using copyrighted work and intellectual property to train AI systems.

(Editors’ Note - we noticed not many people were watching our case study video. We made them shorts. You can still watch the full video at the bottom. - SF)

At TIKI, we’re helping companies stay ahead of the game and future-proof their generative AI products with the use of our data licensing platform. Let’s take Spotify as a simple, easy-to-understand example.

What We Built

Say Spotify wants to implement a new generative AI product feature for their users. Using text prompts, they can quickly generate brand new songs based off their favorite artists or listening history…songs that sound like Drake, or even a “posthumous” rendition of “Shake It Off” by Kurt Cobain.

Using TIKI technology, Spotify can present an offer to all artists on their platform which allows them to opt in or opt out of their catalogue being used to train the AI that results in the generative Kurt Cobain and Drake songs. By opting in, TIKI creates immutable contracts for each individual song in an artists’ catalogue.

Cryptographic hashing powers the immutability of the contract, and each song becomes legally binding contract between the artist and Spotify: Spotify gets the data to train their AI, and the artists get paid out royalties when their music is used in a creative output resulting from a user prompt.

Spotify (or any company) can connect the dots between prompts and royalties paid out using the combination of TIKI’s data licensing technology and their own knowledge graphs. Spotify already has the technology in place to recommend music, now they can just utilize the same technology to assign payouts when a song is created. With each song on the knowledge graph now tethered to an immutable data license, Spotify can map prompts to the songs used to generate the output and pay out royalties appropriately. Nice!

A simple royalty scheme, might define the number of “hops” aka traversals from the keywords in the prompt (i.e. Spotify, make me a Kurt Cobain song that sounds like Taylor Swift), mapping the relative-impact to royalty distribution (most LLMs are a black-box). For example, each generated song might use “10 hops” from the center of keywords Kurt Cobain and Taylor Swift as the payout parameters. Each artist who contributed to the AI, within this band, receives a royalty commensurate with their relative weight (distance from center).

With the legality of generative AI outputs in limbo, this technology can be pivotal in ensuring all training data has an appropriate, immutable legally binding contract attached. Check out how TIKI makes it easy to create high-volume data licenses, offer rewards in exchange for data opt-ins, and automate enforcement right from your stack.

Case Study – Artificial Anarchy

Legal Issues in Generative AI

On February 23rd 2023, the US Copyright Office revoked a copyright registration for the digital comic book “Zarya of the Dawn,” created and registered for copyright by Kristina Kashtanova. The work was registered and previously approved in late 2022, but upon further review, the decision cast down by USCO calls into question whether or not the work was “created” by Kashtanova at all, as the AI generative art program Midjourney was used to generate the images in the comic. While Kashtanova argued that she spent countless hours honing her prompting to Midjourney to ultimately lead to the images used in “Zarya,” USCO ruled users have no copyright claim over the result, as the text prompts do not definitively dictate the result, which is unpredictable.

So, if “Zarya” does not hold enough weight to be copyrighted by Kashtanova, who does the copyright belong to? And what are the ramifications for AI companies and products? These types of questions are at the center of a heated legal battle that will have major ramifications for the entire artificial intelligence industry and the creatives whose work has been used to train AI systems.

In November 2022, two months after Kashtanova’s original copyright submission, GitHub, Microsoft and OpenAI found themselves in a class-action lawsuit over the legality of the training data used to power Copilot, an AI tool developed to assist developers in writing code. Since Copilot’s inception, GitHub has reported that over one million developers have used the technology, resulting in users coding up to 55% faster.

The product uses machine learning algorithms to analyze a developer’s code, and then suggests code to the developer based on a repository of public code scraped from the web. Many of these repositories are published to the web with licenses requiring credit to be given to the original developers when the code is re-used by others. DOE 1 et al v GitHub, Inc. et al claims that because of this, Copilot relies on “software piracy on an unprecedented scale.”

The ramifications of this ruling are potentially industry-shaking. Many AI products and services acquired the data to train their AI using similar practices as Copilot, meaning copyrighted material is constantly being scraped from the web and used to train AI, without the original creators receiving appropriate compensation (or even any credit at all) when the product is monetized. And boy, is it being monetized.

Major Money in Generative Artificial Intelligence

In 2023, time is money. The generative AI industry is worth a boatload of cash for this very reason. The technology has massive potential to completely revolutionize many fields, ranging from music, to medicine, to transportation. Incredibly in-depth, complex outputs can be created from generative AI systems in mere seconds. The power, complexity, speed, and efficiency will only increase as the technology is honed. After all, generative AI as a product is only in its nascent stages, but even still, the global market for generative AI was estimated at around $10.8 billion in 2022. Forecasts for the market in ten years range from over $100 billion to $200 billion.

Technological advancements as well as market demand will greatly factor into the eventual market value in coming years, factoring the productivity, cost savings, and improved quality of work that result from a business perspective.

Another factor? Well, is it legal?

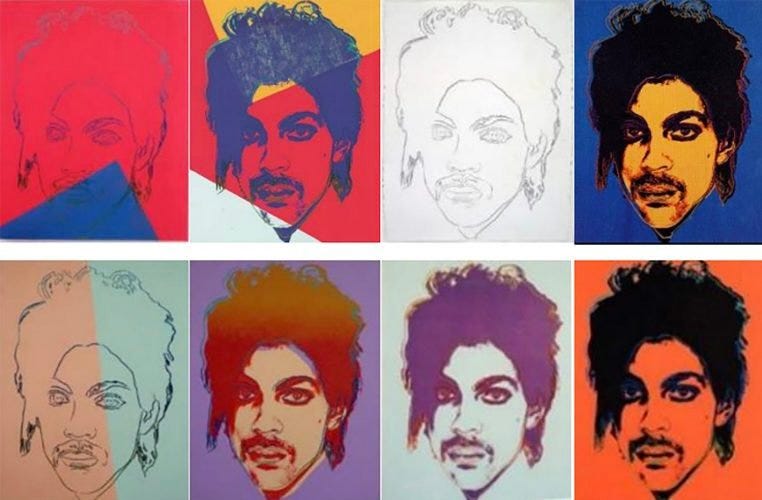

Enter Andy Warhol and Prince, Because, of Course

What is fair use? Well, it’s at the crux of the generative AI legal battle. According to the US Copyright Office, fair use is a “legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances.” This has been the core argument for many AI companies and products. If not fair use, then how in the heck are these products going to be allowed to reach the market and stay there?

In 2019, OpenAI commented to the US Patent and Trademark office that using machine learning algorithms that analyze copyrighted data to train AI programs should constitute fair use, arguing that a contrary legal precedent would have “disastrous ramifications,” and “severely hinder creative AI research.”

Due to the lack of current legal precedence, the generative AI world is essentially the wild, wild west. While the law remains unclear, companies are cashing in, but as we already know, the lawsuits are starting to filter in. As it stands, the fair use defense is being argued when it comes to whether or not generative AI creations fall under copyright law. Whether this argument holds up may be dependent on a ruling involving two late, great artists: Andy Warhol and Prince.

The Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith revolves around artwork created by Warhol that used actual photographs of the late musician Prince. In the case, Lynn Goldsmith, famous for photographing rock stars, argues that photographs she took for Newsweek of Prince in 1981 were used without license in 2016 when Conde Nast, parent company of Vanity Fair paid the Andy Warhol foundation to run the Warhol’s 1984 artwork, which used Goldsmith’s photographs as direct inspiration. The result of this lawsuit could have major ramifications when it comes to generative AI art, as extremely similar questions regarding fair use come in to play.

“Fair Learning,” a 2020 legal paper written by scholars Bryan Casey and Mark Lemley, has become a major reference point for the fair use argument. Speaking about the datasets used to train AI systems, the pair wrote, “there is no plausible option simply to license all of the underlying photographs, videos, audio files, or texts for the new use.” According to them, disallowing fair use and allowing copyright claim would effectively ban the use of these materials altogether. They believe that allowing for fair learning not only promotes innovation, but also leads to the creation of more advanced AI systems.

Regardless of outcome, there will still be unanswered questions when it comes to generative AI. If the Warhol Foundation’s use of Goldsmith’s Prince art falls under fair use, the industry can breathe a bit of a sigh of relief, but that verdict will not account for the thousands, if not millions of creatives whose work is used to train AI models, and who, as of now, do not receive compensation for their work’s role in the AI’s outputs.

But what if there is a way to license the data used to train AI? Similar solutions have arisen in the past, with music licensing being a major example.

Metallica is (or, was) Pissed (And Dr. Dre too. And a lot of others)

Music licensing has tons of parallels to our current artificial intelligence conundrum; in the 2000s music pirating software such as Napster, Limewire, and Kazaa brought about unprecedented access to music, though it was completely illegal. These peer-to-peer file-sharing services allowed individuals to share music, files, and lots of computer viruses to each other over the internet. The legal implications were obvious and similar to the ongoing issues with AI products: there was rampant sharing of copyrighted material without permission from the owners.

Eighteen different record companies, led by A&M Records and represented by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and others sued Napster. A&M Records, Inc. v. Napster Inc. was argued in late 2000 and decided in early 2001. The RIAA argued that Napster and similar services were facilitating illegal distribution of copyrighted material and causing significant financial harm to artists and record labels. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld a district court’s decision that Napster could be held liable for violating copyright via contributory and vicarious infringement.

Soon after, Metallica sued Napster. Dr. Dre and others followed. In the Metallica case, the judge ruled Napster to place a filter on its software that removed all copyrighted songs from Metallica within 72 hours or be taken down. Napster reached a settlement with both Metallica and Dr. Dre in 2001 which resulted in Napster disallowing music being shared from artists who did not consent to their work being shared, with Napster sending out $26 million to Metallica and other artists. Napster would then go on to lose multiple other lawsuits in a short time period, and filed for bankruptcy in June of 2002.

Out of the ashes of these platforms came the likes of Spotify and Apple Music, which succeeded in creating something more convenient than piracy, all while keeping it legal. Companies brought about licensing deals and added the music to their libraries with consent from the artists. They then combined them with convenience and accessibility such as easy-to-use features, curation, and personalization to help them gain a loyal and dedicated user base. Again, all while keeping it legal.

Can the same be done for generative AI produced work?

Companies Attempt to Mitigate Damages

As it stands, there are a few instances of companies taking preventative approaches to the copyright issue, attempting to the best of their abilities and resources to future-proof their technology.

Shutterstock set up a fund which compensates artists when their work is used to train AI, though the fund does not work retroactively. Those whose work had already been scraped and used prior are still without compensation, and other than a text warning on the Shutterstock website, nothing is stopping companies from scraping its library.

"The Stack" is a dataset used to train AI that was created to avoid any copyright issues. It only contains code with open-source licenses that are highly permissive and allows developers to easily remove their data if requested. Its creators stated that “one of our goals in this project is to give people agency over their source code by letting them decide whether or not it should be used to develop and evaluate LLMs [language learning models], as we acknowledge that not all developers may wish to have their data used for that purpose.” They are proponents of their data and similar datasets to be used to help shape multiple industries.

Other companies are taking an even more defensive approach. Getty Images, for example, recently prohibited AI-generated content from being hosted on their cite, citing massive legal risk and implication that could surface in the near future. Safe to say they have been following the cases involving Microsoft, OpenAI, GitHub, Andy Warhol, Prince, and many, many others.

As recently as last week, the wild west has been made a little less wild due to potential legal rulings. The European Union proposed new copyright rules as part of their AI Act that will force companies to disclose any copyrighted materials used to train their systems. What happens when the original owners find their works have been used in datasets to train AI, especially if those AI products then generated revenue? Probably a whole lot more lawsuits. We can already see the rumblings in the music industry, which is bad news for fledgling AI company, Artificial Intelligence.

(Editors’ note: some people have been confused as to whether the companies we feature in our case studies are real. In this example, we mention Artificial Anarchy and Spotify. One of these is real, one of them is not, though it is directly inspired by a real project.We apologize for any previous confusion. – SF)

Artificial Anarchy Built Something Cool…Can they Productize It?

Artificial Anarchy came to be mostly as a research project between a music producer friends who were messing around with their machine learning programs. Huge fans of the punk genre, they spent countless hours training a generative AI model that created songs that sound exactly like the punk band NOFX. Other than being fans of the band, they figured a genre centered around three chords would be a solid start to testing their AI. After countless training hours and years of hard work, they were able to create an endless stream of songs that sounded just like NOFX. While there were rough spots on the product, the core technology worked. They could train their AI on any artist’s catalogue and the output sounded very similar to the original artist. They launched a free digital radio station and streamed generative AI NOFX songs, constantly generating and always new, on the airwaves.

In the early stages of the 2020s, the friends realized that their work could have product-market fit. Generative AI songs spread across the web in the early years of the decade, and picked up tons of steam in late 2022 and early 2023.

Most prominently: Drake. The song “Heart on my Sleeve” was streamed millions of times on TikTok, Spotify and other platforms in April 2023 before swiftly being taken down. The song featured AI vocals from Drake and the Weeknd that were nearly identical to the original artists’ tone and cadence. Soon music fans were creating and uncovering songs sounding just like the industry’s biggest stars, from Kanye West, to Taylor Swift, to Ariana Grande, to deceased stars such as the Notorious B.I.G., Tupac, and Freddie Mercury.

Artificial Anarchy kept tabs on all of the music, but didn’t think they had any merit releasing their AI as an official revenue-generating product. First off, as developers and producers themselves, they were aware of the legal and ethical implications. Second of all, to date they had only really tested it on NOFX and some generic death metal, though they knew it would work on anything, from music to audiobooks to podcasts.

After the hoopla in accordance with “Heart on My Sleeve,” they noticed some trends in the industry worth noting. First, indie musician Grimes went on record stating that she would split royalties 50% with any AI song that gained commercial success using her voice or music. First NOFX and death metal…next Grimes?

Researching more, they learned of artist Holly Herndon and her product, Holly+, an AI version of herself which allows other artists to make music with her voice. She decentralized access, utilizing a DAO, which ingests profits from Holly+ AI and makes decisions on tools created from it as well as its use.

The Problem

While Grimes and Herndon gave hope to Artificial Anarchy, the rest of the industry didn’t seem so receptive.

UMG (Universal Music Group) said in a media statement, "The training of generative AI using our artists' music" represented "both a breach of our agreements and a violation of copyright law." Their CEO and Chairman Sir Lucian Grainge went on to note “the recent explosive development in generative AI will, if left unchecked, both increase the flood of unwanted content hosted on platforms and create rights issues with respect to existing copyright law in the US and other countries – as well as laws governing trademark, name and likeness, voice impersonation and the right of publicity,” adding that “should platforms traffic in this kind of music, they would face the additional responsibility of addressing a huge volume of infringing AI-generated content,” and that “[UMG] have provisions in our commercial contracts that provide additional protections.”

With a behemoth like UMG having these sentiments, it’s safe to say other major players feel the same.

Despite the negative press, the encouragement of artists like Grimes and Herndon, who rely on independent means to release their music, has driven Artificial Anarchy to seek productization of their AI. There are potentially thousands of artists, especially indie artists, who would consent to having their music licensed to be part of the datasets used to train generative AI products. But how would they license all of the music? According to Casey and Lemley’s “Fair Learning” paper, there’s no plausible way to license all that music at scale. Unless, of course, there was a plausible way.

The Solution

(for an more in-depth breakdown, head to the top of this article!)

So the team came to TIKI for assistance. Using TIKI’s data licensing software, every song in a catalogue can be licensed and indexed in seconds with appropriate enforceable terms and conditions, constantly updated in real-time, when necessary. The team at Spotify found fame through licensing agreements combined with personalization. They’ve already got a knowledge graph to combine with the licenses to connect the dots between prompts and royalty payouts. How about a brand new feature that allows users to create their own custom songs based on their favorite artists, leveraging Artificial Anarchy’s AI model and TIKI’s data licensing software. Licensing, personalization and customization worked before to the tune of nearly 500 million monthly active listeners. What will this new feature mean for Spotify? For Artificial Anarchy? For music fans everywhere?

Let’s hope to find out!

More generative AI cases:

Brilliant idea. Did you pitch Spotify?